The Power of Film Propaganda - Triumph of the Will (1935)

- Dom Todd

- Nov 18, 2023

- 10 min read

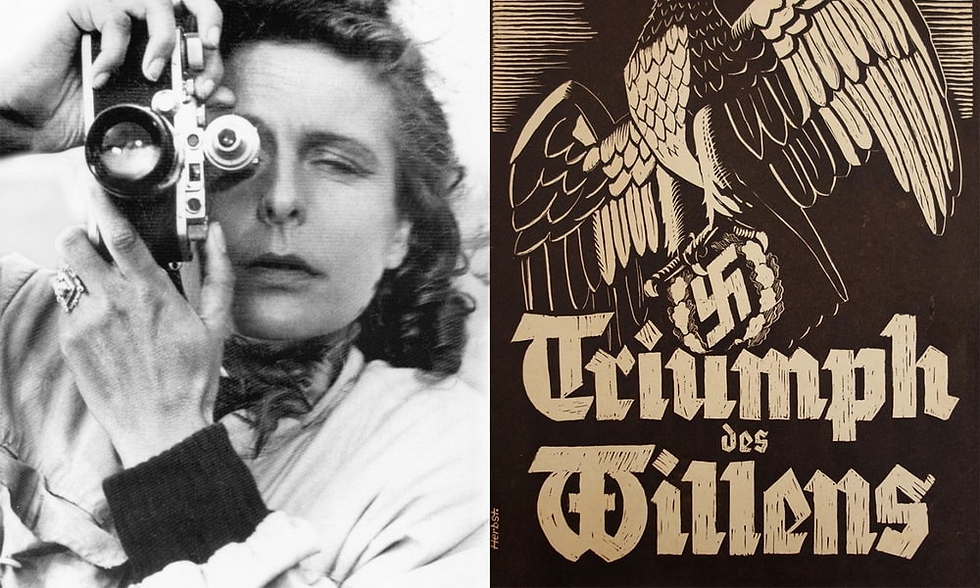

Propaganda is everywhere. The word can basically be applied to any kind of media that's designed to change the way you feel or influence your actions, and this means it can range from simple things like environmental messages, adverts and political slogans to far more harmful ideas, like appeals to authoritarianism or the systematic dehumanisation of entire groups of people. Since its inception, the cinema has played a role in the dissemination of propaganda, of all kinds, and the silver screen has frequently found itself as the battleground in the modern war of information. One of the most famous propaganda films ever made is Triumph des Willens (Triumph of the Will (Dir. Leni Riefenstahl)) from 1935. It wasn't the first propaganda film, but it was a huge leap in the scale and scope of cinema as a means of political persuasion; and it showed just how effective the art form can be in influencing and even brainwashing its audience. Although the film is praised for revolutionising propaganda, it really invents very little for itself, instead, borrowing on techniques that date right back to the origin of cinema and magnifying them with an unprecedented level of top political support and a huge production budget. How was this infamous film used by the Nazi regime to further their anti-Semitic and authoritarian ideology and how does this relate to the power of propaganda and its influence?

To give context and understanding, let's look back at the origins of cinema as a tool of propaganda and how it's been used by governments and individuals to influence the hearts and minds of its audience. Propaganda films go right back to the beginning of cinema. To give you an idea of just how far back, the Lumiere brothers displayed the first ever film projection in 1895, and what are considered the first propaganda films were being produced by Vitagraph in the form of newsreels. Three years later, in 1898, one such film was Tearing Down the Spanish Flag (Dir. J. Stuart Blackton, 1898), and although it only lasts thirty-nine seconds and is extraordinarily simple, it can tell us quite a bit about the nature of propaganda. For one thing, although it was purported to be shot in a real battle and it was displayed mixed in with the real footage from the war, it was quite obviously faked, filmed in a studio in New York; it also reveals a second truth about the nature of propaganda: the only important information that the audience receives is what's contained within the borders of the frame. This might seem obvious, but let's examine what it means. A Spanish flag goes down and is replaced with an American flag; it's designed to give the audience a euphoric patriotic sense of victory, but the film is stripped from its context. It tells you nothing of the bloodshed, poverty or death caused by the war. Instead, it instils in the mind of its audience the idea of victory while avoiding the inevitable human cost that it would require. This is one of the simplest ways that propaganda can work. By controlling the narrative, the film makers can control the audience's emotional response and, in the long run, condition in them a deep held belief or outlook. In this case, a jingoistic sense of victory, leading to support for an overseas war.

Later during World War One, the real development of wartime propaganda came not from the Germans, but from the British. One of the first acts of military action in World War One was to sever the transatlantic cables connecting Germany and America. The British knew very well that success in the war would rely on turning the American public opinion against the Germans and ensuring the strength and stability that came from having America as both a trading partner and a military ally. The British government set up the National War Aims Committee to produce propaganda of all kinds, including the immensely popular newsreel which brought images from the front into theatres at home, inserting patriotic sentiment into mass entertainment. The British government even went as far as to hire American filmmaker DW. Griffith to produce the propaganda film Hearts of the World (Dir. DW. Griffith, 1918) in which an American and his French lover are brutalised by the German army. World War One was a new kind of war; victory would require both the combined effort and sacrifice of the entire country and therefore wartime propaganda would be aimed at the whole population to sacrifice for the war effort.

Over in America, stars of the day like Douglas Fairbanks and Charlie Chaplin appeared in trailers, encouraging the public to buy war bonds; and a newly established Hollywood worked with the War Cooperation Committee of the Motion Picture Industry to produce films like The Little American (Dir. Joseph Levering & Cecil B. DeMille, 1917) and The Unbeliever (Dir. Alan Crosland, 1918) to build anti German sentiment. The same messages and the same depiction of the German people was repeated again, and again. The British and American War films established what would become one of the most important aspects of the propaganda film: the constant reinforcement of “the message” continually hitting the same emotional responses and repeating the state approved narrative until the audience believed it.

Once the First World War ended, the British government scaled back their propaganda offices. But in 1917, a newly formed Soviet government in Russia would take propaganda to new artistic heights with conjuring of Agitprop, a combination of agitation and propaganda to help educate the Soviet people in what the government wanted them to believe. Facing a largely illiterate population who spoke a variety of different languages, the Soviets turned to cinema to create a universal language. In 1919 the Soviets nationalised the film industry and established the Moscow Film School and it saw the development of new cinematic language in theory from the Kuleshov Effect to Montage Theory. Sergei Eisenstein used these techniques to spread the Soviet message of rebellion in Battleship Potemkin (Dir. Sergei Eisenstein, 1925) and glorify the 1917 Soviet Revolution in October (Dir. Sergei Eisenstein, 1928). Intellectual Montage allowed film makers to implant ideas almost subconsciously into films, the oppressive Tsarist forces beating down on unarmed civilians gave the viewer an insight into the government's brutality, regardless of which language you spoke. Films like these legitimised the revolution and therefore legitimised the Soviet regime. New theories of cinematic metaphor allowed propaganda to be easily inserted into popular entertainment, such as one of the first feature length science fiction films in 1924, Aelita (Dir. Yakov Protazanov) which saw a Soviet style rebellion against the ruling class of Mars, thereby proving to the glory of the revolution that took place on Earth.

The Nazi regime took power in Germany in 1933, and they set about establishing the most comprehensive and all-encompassing propaganda machine that the world had ever seen. World War Two wasn't just a war of military might, it was a war of ideologies between the democratic freedom of the Allies and the authoritarianism of the Third Reich. Hitler was well-aware of the power of propaganda, so much so that he dedicated two full chapters of his book Mein Kampf (1925) to its usefulness. He highlights the effectiveness of Allied propaganda in winning the First World War, praising its repetition repeatedly appealing to the emotions of the British people, and painting the Germans as beastly Huns. He also looked to the masterful use of propaganda in the Soviet regime in appealing to all aspects of society.

In Mein Kampf Hitler outlines what he sees as the key principles of effective propaganda: It should be focused and one sided; it should be consistent across multiple platforms; it should never be weakened by objective analysis, and it should be boiled down to a few key themes or phrases which are continually repeated. He used this style of propaganda first to justify his dictatorship and later to legitimise one of the worst atrocities in human history. In book eight of Republic (Plato, c. 375 BCE.), philosopher Plato describes a fictional Democratic city. He asserts that the freedom of democracy could be undermined by a cunning manipulator who, by using the language of freedom and the disguise of the people's protector, coerces them into voting against their own self-interest, willingly trading their democracy for authoritarianism. In the case of the Third Reich, this cunning manipulator wasn't just Hitler but Joseph Goebbels, head of the Nazi Ministry of Propaganda.

What separated the Nazi propaganda machine from the British or American was that the Nazis operated total media control with the goal of complete indoctrination of all its citizens. Every meaningful aspect of culture that could be consumed from the press, radio, theatre, art, music and cinema was produced or approved by the regime, and it all pulled towards the same goal of conditioning the German people into believing the racist authoritarian ideology of the party. It's the propaganda of Goebbels that gives us the images of Nazi Germany that we have today. He's responsible for creating the depiction of Hitler as a master orator and a genius political tactician and his campaign of indoctrination helped transition Germany from the relative freedom of the Weimar Republic to the tyranny of the National Socialists and one of the tools that he used to do that was Triumph of the Will.

Triumph of the Will is a semi documentary take on the sixth Annual National Socialist Conference in Nuremberg in 1934 by director Leni Riefenstahl. It covers four days' worth of speeches, parades, and citywide celebration. It's edited together out of hundreds of hours of footage, and it unveils the core message of the conference without commentary or intertitles; although it's often praised as revolutionising the art of film propaganda, it in fact adds very few techniques its own.

Sometimes when looking for the aims of a piece of propaganda, you needn't look much further than the aims of the people who produced it. Having secured political power, Hitler looked to use propaganda to downplay the violent treachery that gave him his position and inspire unconditional loyalty and support for him and his party. Although it's presented as an objective “fly-on-the-wall" documentary, this is the true aim of the Triumph of the Will.

The opening shots give us a glimpse into the kind of imagery that we can expect from the rest of the film. Aerial shots of pure white cloud give way to the city of Nuremberg; we see the St. Lorenz Cathedral draped in the Nazi flag and, immediately, the parallel is drawn between the regime and religion. Then, as the plane lands, Hitler emerges as if descending from heavens; the very first depiction of Hitler engenders him with the divine status. Riefenstahl shows seemingly endless crowds of loyal, awestruck supporters all looking to Hitler as saviour. Hitler is adored by all, adults and children, civilian and military; the arrival of Hitler in Nuremberg is that of a messianic figure. Borrowing from British propaganda, this point is hammered home with shots of seemingly millions of supporters again and again. Low shots of Hitler paint him as the supreme leader, towering above the masses, almost God-like in his unchallenged authority. The film hits the same notes over and over: camaraderie, obedience, loyalty. Furthermore, intellectual montage lifted directly from Sergei Eisenstein and Soviet propaganda show Hitler as he walks through the crowd, shaking hands with his troops intercut with repeated artillery fire. The parallel is clear: through unity and loyalty to Hitler comes military strength and victory. The strength of the German military is repeatedly showcased through parades and demonstration, even the Reich Labour Service operate with military efficiency. Military superiority isn't just implied, it's inevitable. This is the depiction of a holy army graced by God with their racial superiority.

A common tactic of propaganda is to create a nostalgic appeal to a prior golden age and suggest that this former glory can somehow be recaptured. In the case of the Triumph of the Will, this “golden age” is Germany from before World War One. The film opens at the title card, reminding the audience of the horrors of the war that started twenty years earlier. The film introduces people marching in traditional German dress and as they shake hands with Hitler the suggestion is that this is the return of Germany's pre-war glory. Building on this we're constantly reminded of the sacrifice made by those who fought in the war; traditional folk tunes are slowly replaced by more militaristic music; comparisons are drawn between sacrificing yourself for your country and immortality. The film is calling on Germany's young to give themselves for the cause of the Third Reich and, with Hitler, rebuild Germany like a phoenix from the ashes. The entire film is pointed to one message, and it can be summed up by the closing lines of the film: “Hitler, Hitler, Hitler...”

Triumph of the Will is often heralded as a crowning achievement in cinematic propaganda, but at its heart it's no more than an elaborate version of Tearing Down the Spanish Flag. Though it borrows from the authenticity of the documentary medium and with Riefenstahl’s insistence that the film was an unbiased representation of true events, the truth is that the whole conference was staged and orchestrated specifically for the film; Riefenstahl helped organise events, had a hand in the overall design and even had bridges, towers and ramps built in Nuremberg’s city centre to magnify the effect of the conference on screen. The film is a carefully staged and managed event, designed to pull the National Socialist ideology from its context; all the information is contained within the frame and anything external to the border to the screen is unimportant. The film does not deal with policy or argument; every frame is designed to appeal to emotion while wilfully disregarding the violent thuggish behaviour that aided Hitler ascertain power; though the film does mention the ideas of racial purity, it purposely does not reflect the persecution of Jewish, black, disabled, homosexual or Roma people that was already well underway by 1934.

This kind of propaganda is so effective that even today, more than eighty years later, there are still people who purposely disregard the unprecedented horror of the Holocaust. However, in all, far from the genius work of art that its reputation espouses, Triumph of the Will stands as a testament of the ability of blunt, emotional attacks to overwhelm rationality and it is evidence to the necessity of media criticism. Propaganda still affects us every day; although the technology behind it is much more developed, it still operates on the same basic principles.

Bibliography:

Hitler, A. (1925) Mein Kampf

Plato (c. 375 BCE) Republic

Ebert, R. (2008). Triumph of the Will (1935). Chicago Sun-Times.

Barsam, R. (2015) Filmguide to Triumph of the Will

Filmography:

Triumph of the Will (Dir. Leni Riefenstahl, 1935)

Tearing Down the Spanish Flag (Dir. J. Stuart Blackton, 1898)

Hearts of the World (Dir. DW. Griffith, 1918)

The Little American (Dir. Joseph Levering & Cecil B. DeMille, 1917)

The Unbeliever (Dir. Alan Crosland, 1918)

Battleship Potemkin (Dir. Sergei Eisenstein, 1925)

October (Dir. Sergei Eisenstein, 1928)

Aelita (Dir. Yakov Protazanov, 1924)

Comments